Google, Netflix, ChatGPT with web search. What do they have in common? A ranking algorithm decides what you see first. Not what exists. What you see.

LTR kept coming up while our team debugged why the RAG pipeline returned garbage for certain queries. The algorithms weren’t hard to find. But almost nobody building AI applications seemed to understand the ranking layer underneath.

Your RAG pipeline is only as good as your ranker. Feed an LLM irrelevant context, and no amount of prompt engineering saves you. The “R” in RAG is a ranking problem wearing a retrieval costume.

This article covers the fundamentals: why ranking differs from classification, how LambdaMART actually works, and what all of this means for RAG. Skip it at your own risk.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Why Ranking Is Not Classification

And Why That Matters

Standard machine learning predicts a single value per instance. Spam or not spam. Cat or dog. Price estimate. Ranking is different.

Given a query and a set of documents, produce an optimal ordering where the most relevant items appear first. Here’s the thing: absolute scores don’t matter. Only relative ordering does. A model that assigns relevance scores of 0.7 and 0.5 to two documents produces identical rankings to one assigning 0.001 and 0.0005. Yet standard regression metrics would heavily penalize the second model.

Consider two models scoring a relevant document against an irrelevant one for the same query. Model A assigns 0.1 to the relevant document and 0.2 to the irrelevant one. Low error on the scores themselves, but wrong order. Model B assigns 0.7 to the relevant document and 0.5 to the irrelevant one. Higher absolute error, but correct ranking.

Model B wins. Users don’t see scores. They see the list.

You can’t simply minimize mean squared error because lower regression error doesn’t guarantee better rankings. LTR requires specialized loss functions that optimize for what we actually care about: the quality of the ranked list itself.

The Three Paradigms

Pointwise, Pairwise, and Listwise

The field converged on three approaches. Each trades off simplicity against computational cost and theoretical soundness.

Pointwise: The Simplest Path

Pointwise methods treat ranking as regression. Score each document independently, sort by score, done.

No specialized loss functions or architectures required. Got a working classification pipeline? You’ve got a ranker.

Problem is, scoring documents in isolation ignores comparison. Nothing forces relevant docs to score higher than irrelevant ones for the same query. It’s optimizing the wrong objective and hoping the rankings work out anyway.

Sometimes they do. Often enough to be useful for prototypes, not reliable enough when ranking quality actually matters.

Pairwise: Comparing Documents Directly

Pairwise methods reframe ranking as binary classification over document pairs. Given documents A and B for a query, predict which should rank higher. Training data transforms into pairs: (query, doc_A, doc_B, label) where the label indicates A > B or B > A.

The seminal RankNet algorithm from Microsoft Research (2005) applies cross-entropy loss to these pairwise comparisons, training neural networks to minimize incorrectly ordered pairs. The key advance: pairwise comparison is closer to the true ranking objective than independent scoring.

The cost is computational. For n documents per query, you’re looking at O(n²) pairs. A query with 100 candidate documents generates nearly 5,000 training pairs. Scale that across millions of queries and storage becomes a real concern.

There’s also no consideration of the full list structure. A model might correctly order documents at positions 1–2 while catastrophically failing at positions 5–6. Both contribute equally to the pairwise loss, but the first matters far more to users who rarely scroll past the first few results.

Listwise: Optimizing What We Actually Measure

Listwise methods optimize the entire ranked list directly. ListNet models the probability distribution over all possible permutations using the Plackett-Luce model, minimizing KL divergence between predicted and ground-truth distributions. AdaRank directly optimizes information retrieval metrics like NDCG through boosting.

These approaches are theoretically superior. They optimize what we actually measure. But they face a fundamental obstacle: metrics like NDCG are non-differentiable step functions. The ranking position of a document changes discretely as scores cross each other. You can’t compute gradients for standard backpropagation.

So how do you actually optimize for NDCG?

Lambda Gradients

The Trick That Makes Listwise Work

The breakthrough came from LambdaRank (2006) and its gradient-boosted variant LambdaMART (2010). The trick is almost embarrassingly simple.

Instead of deriving gradients from a cost function (which we can’t do for non-differentiable metrics), define the gradients directly as the forces that push documents toward their correct positions.

Think of it like physics. Skip the energy function, just measure the forces. We know which direction documents should move (toward their correct positions) and we can calculate how much the ranking metric would improve if they moved. That’s enough.

The lambda gradient for a document pair combines RankNet’s pairwise gradient with the actual metric change:

λᵢⱼ = σ(sⱼ — sᵢ) × |ΔNDCG|

Where |ΔNDCG| is how much NDCG would change if documents i and j swapped positions. Documents that would significantly improve NDCG if promoted get larger gradient magnitudes. Documents near their correct position get smaller gradients.

This bypasses non-differentiability by computing gradients after sorting. The metric change is calculable even though the metric itself isn’t differentiable with respect to scores.

LambdaMART combines these lambda gradients with gradient-boosted decision trees, creating an ensemble where each tree fits the residual gradients from previous trees. This algorithm won Track 1 of the 2010 Yahoo Learning to Rank Challenge and remains the production workhorse at major search engines today.

It’s available in XGBoost (rank:ndcg objective), LightGBM (lambdarank), and CatBoost (YetiRank). Here’s what it looks like in practice:

from lightgbm import LGBMRanker

ranker = LGBMRanker(objective="lambdarank", metric="ndcg")

ranker.fit(

X_train, y_train,

group=query_doc_counts, # [10, 15, 8] = 3 queries with 10, 15, 8 docs

eval_set=[(X_val, y_val)],

eval_group=[val_query_counts],

eval_at=[5, 10] # NDCG@5, NDCG@10

)The group parameter is crucial. It tells the ranker which documents belong to each query, enabling list-aware optimization. Without it, you’re back to pointwise methods.

Measuring What Matters

Ranking Evaluation Metrics

Before going further, we need a shared vocabulary for measuring ranking quality. Different metrics capture different aspects of what “good” means.

NDCG: The Gold Standard

NDCG (Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain) handles graded relevance with position-dependent weighting. Not all relevant documents are equally relevant. Some are perfect matches, others are tangentially useful. NDCG captures this nuance.

The formula applies a logarithmic discount to positions:

DCG@k = Σᵢ (2^relevanceᵢ — 1) / log₂(1 + i)

Documents at position 1 get full credit. Documents at position 2 get discounted by log₂(3) ≈ 1.58. By position 10, the discount is log₂(11) ≈ 3.46. This reflects how users actually behave: they pay far more attention to top results.

Normalizing against the ideal ranking (what NDCG would be if we sorted perfectly) produces scores in [0, 1]. An NDCG@10 of 0.85? You’re getting 85% of the best possible ranking in your top 10.

NDCG dominates academic research because it handles multiple relevance levels and penalizes relevant documents appearing lower in rankings. If you’re only tracking one metric, make it NDCG.

MRR: Where’s The First Good Result?

MRR (Mean Reciprocal Rank) answers a simpler question: on average, how far down is the first relevant result?

MRR = (1/|Q|) × Σ(1/rankᵢ)

If the first relevant result is at position 1, that query contributes 1.0. Position 2 contributes 0.5. Position 10 contributes 0.1.

This matters enormously for “I’m feeling lucky” scenarios where users want exactly one good answer. This is directly relevant to RAG systems selecting context for generation. If your RAG pipeline takes the top-1 result, MRR tells you how often that result is actually relevant.

MAP: The Precision-Recall Balance

MAP (Mean Average Precision) computes average precision across all recall levels for binary relevance, then averages across queries. Basically the area under the precision-recall curve. Easier to explain than NDCG, but you lose graded relevance.

Precision@k and Recall@k

Precision@k and Recall@k just count relevant items in the top-k. Precision@10 = 0.3 means 3 of your top 10 are relevant. No position weighting though.

For RAG applications, Recall@k matters when you’re retrieving candidates for re-ranking. If your first-stage retrieval misses relevant documents entirely, no re-ranker can save you.

From BM25 to BERT

The Neural Revolution

Traditional LTR models consume feature vectors, not raw text. Before neural approaches, feature engineering was the competitive dimension. Teams would iterate endlessly on combinations of TF-IDF scores, BM25 variants, document length normalization, and link analysis signals.

The LETOR benchmark datasets standardized 46 features covering term frequencies computed across document zones (title, body, anchor text), plus PageRank and other signals. Building a ranker meant building a feature pipeline.

Neural models changed the game by learning features directly from text.

DSSM: The First Neural Ranker

DSSM (Deep Structured Semantic Model) from Microsoft in 2013 pioneered neural ranking by mapping queries and documents into a shared semantic space via multi-layer perceptrons, then computing cosine similarity.

The idea was to capture semantic matching. “Best programming language for beginners” should match documents about “easy to learn coding languages” even without word overlap.

It worked, partially. But ignoring exact term signals hurt. Queries with specific product codes, technical terms, or proper nouns lost critical information. The model learned meaning but forgot words.

Then BERT Happened

The transformer revolution arrived in January 2019 when Nogueira and Cho applied BERT to passage re-ranking, achieving a 27% relative MRR@10 improvement on MS MARCO, the largest single jump in the benchmark’s history. Every subsequent top submission leveraged BERT or its variants.

The key was cross-attention. BERT processes query and document together, allowing each query token to attend to all document tokens and vice versa. This captures interactions that separate encoders miss: whether a specific query term appears in a specific document position, whether the document’s claims support or contradict the query’s premise, whether the tone matches the intent.

But this power comes with a cost that defines modern retrieval architecture.

Cross-Encoders vs. Bi-Encoders

The Fundamental Tradeoff

This architectural distinction is essential for building production systems. Get it wrong and you’ll build something that’s either too slow to use or too inaccurate to matter.

Cross-Encoders: Maximum Accuracy, Minimum Scale

Cross-encoders concatenate query and document into a single input:

[CLS] query tokens [SEP] document tokens [SEP]Full transformer cross-attention captures fine-grained interactions. The [CLS] token representation feeds a classifier producing a relevance score.

Cross-encoders achieve the highest accuracy. They also can’t scale.

Every query requires n full transformer passes for n candidate documents. You cannot pre-compute document representations because the representation depends on the query. BERT inference takes roughly 5–20ms per document on GPU. Against a corpus of 1 million documents, that’s 5,000–20,000 seconds per query. Not viable.

Bi-Encoders: Scale Everything, Sacrifice Nuance

Bi-encoders process query and document through separate encoders, producing independent embeddings combined via dot product or cosine similarity.

Documents can be embedded offline and indexed in a vector database. A query requires one encoder pass plus efficient approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search against the entire corpus. Sub-100ms latency against millions of documents is routine.

The cost: no cross-attention means missing nuanced query-document interactions. The model must compress all document information into a fixed-size vector before seeing the query. Some information inevitably gets lost.

The Numbers That Matter

| Aspect | Cross-Encoder | Bi-Encoder |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Higher | Lower |

| Latency per document | ~5-20ms | Sub-millisecond (pre-computed) |

| Scalability | Poor (linear in corpus size) | Excellent (ANN search) |

| Use case | Re-ranking top-100 | First-stage retrieval over millions |

This tradeoff is why modern systems use both.

Two-Stage Retrieval

The Architecture That Powers Production RAG

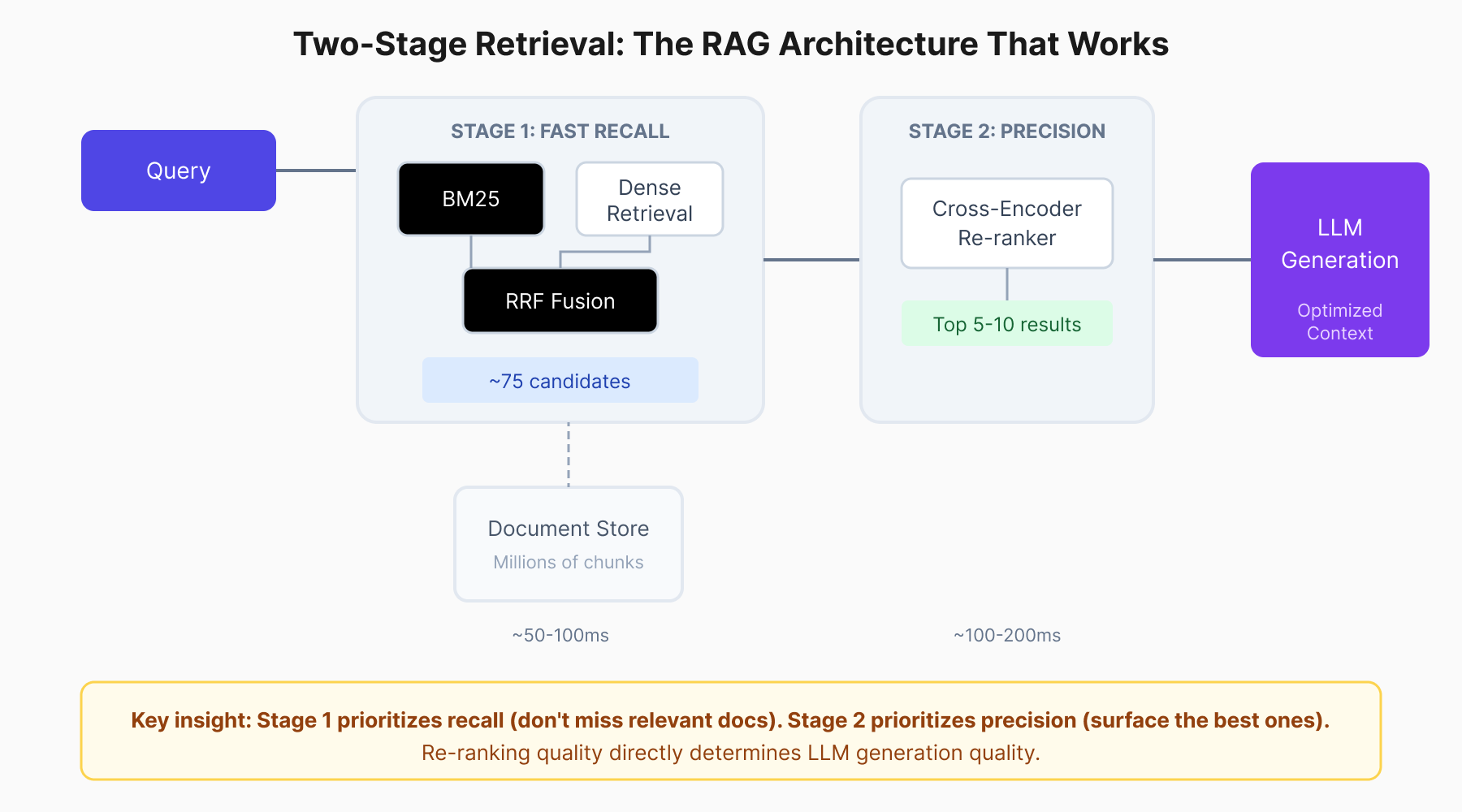

The solution that emerged, and now dominates production systems, is two-stage retrieval.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Two-stage retrieval balances speed and accuracy: fast first-stage recall followed by precise cross-encoder re-ranking.

Two-stage retrieval balances speed and accuracy: fast first-stage recall followed by precise cross-encoder re-ranking.

Stage 1: Fast Recall

Use bi-encoders or BM25 (or both) to retrieve top-50 to top-100 candidates from potentially millions of chunks. This stage prioritizes recall over precision. Missing a relevant document here is fatal. No downstream component can recover it.

Stage 2: Accurate Re-ranking

Apply an expensive but accurate cross-encoder to re-rank candidates down to the top-3 to top-10 that actually enter the LLM context. This stage prioritizes precision. You have 100 candidates; pick the 5 that matter most.

The math works. Given 40 million chunks, applying BERT directly would take over 50 hours per query. Vector search achieves the same candidate retrieval in under 100ms. Cross-encoder re-ranking of 100 candidates adds 100–200ms. Total latency: sub-500ms. That’s production-viable.

For RAG specifically, this architecture is non-negotiable. Research on the “Lost in the Middle” phenomenon shows LLM recall degrades as context length increases. Information buried in the middle of long contexts often gets ignored. You can’t compensate by stuffing more documents into context. You need to stuff the right documents.

Re-ranking is how you find them.

Hybrid Retrieval

Why BM25 Still Matters

A consistent finding across production systems: combining BM25 with dense retrieval beats either alone.

BM25 catches exact keyword matches: product IDs, technical terms, proper nouns, anything that embedding models might not represent well in their vector space. Search for “error code 0x80070005” and BM25 finds that exact string. Dense retrieval? Might give you “permission errors” instead. Semantically close, practically useless.

Dense retrieval handles vocabulary mismatch. “How do I fix a slow laptop?” matches documents about “computer performance optimization” and “Windows startup programs” even without word overlap.

Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) merges results effectively:

score(d) = Σ 1/(k + rank(d, retriever))

With k typically set to 60. Documents ranked highly by both retrievers surface to the top. Documents that only one retriever finds still contribute, but with diminished weight.

A robust RAG pipeline looks like:

- Hybrid retrieval: BM25 top-50 + dense retrieval top-50

- Merge and deduplicate: RRF fusion → ~75 unique candidates

- Re-rank: Cross-encoder reduces to top-10

- Generate: LLM receives optimized context

This isn’t premature optimization. It’s the baseline architecture that works.

Production Re-rankers

Your Options

When you’re ready to add re-ranking to your pipeline, you have three main paths.

Cohere Rerank: Managed Power

Cohere’s Rerank 3.5 provides a managed API at roughly $2 per 1,000 searches (one search = one query plus up to 100 documents). Supports 100+ languages, handles JSON and tables, benchmarks well.

import cohere

co = cohere.Client('your-api-key')

results = co.rerank(

query="What causes memory leaks in Node.js?",

documents=retrieved_chunks,

model="rerank-v3.5",

top_n=5

)No GPUs to manage, solid multilingual support. Downside: you’re paying per query, and that adds up.

BGE Rerankers: Open-Source Production-Ready

BGE (BAAI General Embedding) offers Apache 2.0 licensed rerankers that you self-host. The bge-reranker-v2-m3 handles multilingual queries. The bge-reranker-v2-gemma pushes accuracy higher with a 2B parameter backbone.

from FlagEmbedding import FlagReranker

reranker = FlagReranker('BAAI/bge-reranker-v2-m3', use_fp16=True)

scores = reranker.compute_score([

[query, doc] for doc in candidate_documents

])Self-hosting eliminates API costs but requires GPU inference infrastructure. For high-volume applications, the economics favor self-hosting. For prototypes and moderate scale, managed APIs win on simplicity.

MS-MARCO MiniLM: Lightweight Starting Point

Sentence-transformers provides cross-encoders trained on MS-MARCO that run fast enough for prototyping. The cross-encoder/ms-marco-MiniLM-L-6-v2 at 22M parameters achieves reasonable accuracy. Good enough to validate that re-ranking helps before committing to larger models.

from sentence_transformers import CrossEncoder

model = CrossEncoder('cross-encoder/ms-marco-MiniLM-L-6-v2')

scores = model.predict([

[query, doc] for doc in candidate_documents

])Start here. Move to BGE or Cohere when you need production accuracy.

Fine-Tuning

When Generic Isn’t Good Enough

Off-the-shelf re-rankers optimize for generic web search. Medical, legal, financial, and technical domains have domain-specific relevance criteria, terminology, and document structures that general models miss.

Fine-tuning closes this gap, but the bottleneck is training data.

Synthetic Data Generation

You likely don’t have thousands of labeled query-document pairs. But you do have documents. LLMs can bridge the gap.

The process:

- For each document chunk, prompt an LLM to generate plausible queries that this chunk would answer

- Use another LLM pass (or the same one) to score query-document relevance on a scale

- Sample negatives from other chunks

- Train on triplets (query, positive_doc, negative_doc)

This isn’t perfect data, but it’s domain-specific data. Models fine-tuned on synthetic data consistently outperform generic models on domain benchmarks.

Hard Negative Mining

The secret to effective fine-tuning: hard negatives.

Random negatives are too easy. If you’re training a medical search re-ranker and your negatives include documents about cooking recipes, the model learns nothing useful. It already knows medical queries don’t match cooking content.

Hard negatives are documents that almost match but don’t. Use your current retriever to find top-k candidates for training queries, filter out truly relevant documents, and the remaining high-similarity but non-relevant documents become hard negatives.

Pseudo-code for hard negative mining

for query, positive_doc in training_data:

candidates = retriever.search(query, top_k=20)

hard_negatives = [

doc for doc in candidates

if doc != positive_doc and not is_relevant(query, doc)

]Models trained against hard negatives learn to make fine distinctions rather than obvious ones. That’s what production ranking requires.

The LLM Revolution in Ranking

LLMs changed the game again.

RankGPT: Zero-Shot Ranking That Works

RankGPT demonstrated that GPT-4 can perform zero-shot ranking through instructional permutation generation. Given a query and candidate documents, the LLM outputs a reordered list. A sliding window strategy handles more documents than fit in context.

The result? GPT-4 with zero-shot prompting outperforms supervised systems on TREC, BEIR, and multilingual benchmarks. No training data required. This won an EMNLP 2023 Outstanding Paper Award.

The catch: GPT-4 inference is expensive. For high-volume applications, you need distillation.

Distillation: LLM Intelligence at Deployable Cost

RankVicuna (7B parameters) distilled from RankGPT using GPT-3.5 achieves comparable ranking performance at a fraction of the cost. RankZephyr, fine-tuned from Mistral, achieves state-of-the-art passage ranking while remaining deployable on commodity hardware.

The pattern: use expensive LLMs to generate training signals, then train smaller models to replicate the behavior. You pay the LLM cost once during training, not at inference time.

RankRAG: Unified Ranking and Generation

RankRAG from NeurIPS 2024 takes this further: instruction-tune a single LLM for both ranking and generation. Adding a small fraction of ranking data to training dramatically improves both retrieval and generation quality.

Llama3-RankRAG significantly outperforms GPT-4 on knowledge-intensive benchmarks. Not because it’s a better language model, but because it’s better at identifying which context matters.

This is where the field is heading. The distinction between “retrieval” and “generation” components is blurring. Models that understand both ranking and generation outperform systems that treat them separately.

Framework Integration

Making It Real

Most RAG frameworks now support re-ranking as a first-class concept.

LangChain

from langchain.retrievers import ContextualCompressionRetriever

from langchain.retrievers.document_compressors import CrossEncoderReranker

from langchain_community.cross_encoders import HuggingFaceCrossEncoder

model = HuggingFaceCrossEncoder(model_name="BAAI/bge-reranker-base")

compressor = CrossEncoderReranker(model=model, top_n=5)

compression_retriever = ContextualCompressionRetriever(

base_compressor=compressor,

base_retriever=vector_store.as_retriever(search_kwargs={"k": 20})

)

# Now queries automatically retrieve 20, re-rank, return top 5

docs = compression_retriever.get_relevant_documents("your query")LlamaIndex

from llama_index.core.postprocessor import SentenceTransformerRerank

reranker = SentenceTransformerRerank(

model="cross-encoder/ms-marco-MiniLM-L-6-v2",

top_n=5

)

query_engine = index.as_query_engine(

similarity_top_k=20,

node_postprocessors=[reranker]

)

# Retrieves 20 nodes, re-ranks to 5, passes to LLM

response = query_engine.query("your query")The integration is straightforward. The performance improvement is typically substantial. Expect 10–30% improvement in answer quality for well-structured RAG applications.

The Bigger Picture

The emergence of powerful LLMs hasn’t diminished LTR’s importance. It has amplified it.

RAG systems are fundamentally ranking problems with generation attached. The quality of retrieved context bounds the quality of generated answers. LLMs are too slow and expensive for first-stage retrieval over large corpora. Understanding NDCG, lambda gradients, and cross-encoder versus bi-encoder tradeoffs provides the conceptual foundation to build, debug, and improve modern AI applications.

The connection to RLHF runs deep: the Bradley-Terry model underlying preference learning is a ranking model. Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) and related alignment techniques are conceptually listwise LTR applied to LLM outputs. Understanding ranking fundamentals provides intuition for LLM alignment mechanisms.

The field is converging toward unified systems. Models like BGE-M3 provide dense, sparse, and late-interaction retrieval simultaneously. Frameworks like RankRAG combine ranking and generation in single models. Distillation pipelines transfer LLM ranking capabilities to efficient deployable models.

But the fundamentals remain unchanged. You’re learning a function that orders documents by relevance to a query, evaluated by metrics that weight position, optimized by losses that handle the unique structure of ranked lists.

Master these concepts and you have the tools to build search, recommendations, and RAG systems that actually work. Skip them, and you’re building on sand, hoping the magic of LLMs compensates for retrieval failures it can’t see.

It won’t.